A comparison of recumbent step training and cycling in neurological and geriatric rehabilitation – biomechanical, functional and evidence-based evaluation taking into account logistical and economic conditions

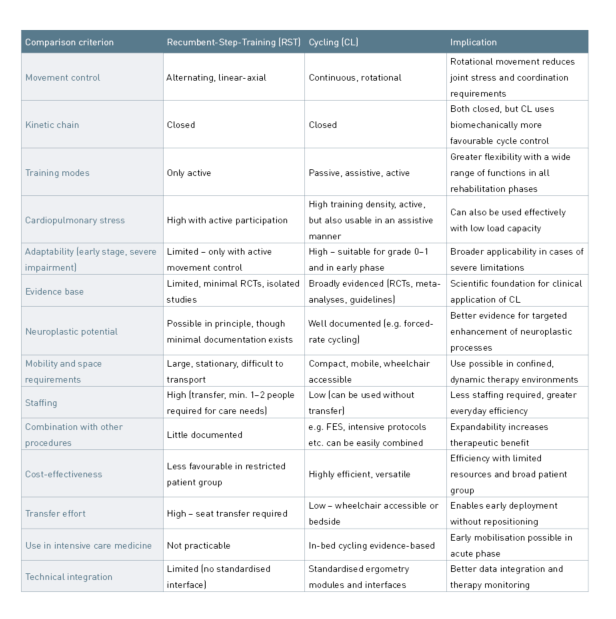

Both forms of training are based on a closed kinetic chain but differ fundamentally in terms of movement control and adaptability. RST generates a linear-axial, alternating extension–flexion of the lower extremities with the feet in a fixed position in a semi-upright sitting position, often combined with arm activity. CL, however, is based on a continuous rotational movement with even load distribution across the entire range of motion and can be applied passively, assistively or actively to the upper and lower extremities.

There is growing evidence in favour of CL, which can be used at an early stage, requires low coordination skills, is gentle on the joints and can be performed with high training density. RST, however, requires higher motor-cognitive skills, is more complex to organise and is less adaptable – especially in patients with severe functional limitations.

CL also offers structural advantages in terms of equipment complexity, space requirements and controllability. Against the backdrop of limited staff resources and infrastructure, the use of RST increasingly raises the question of proportionality in terms of effort and benefit.

This article compares both methods, focusing on biomechanical, functional, practical and evidence-based aspects in neurological and geriatric rehabilitation.

RST is based on the functional coupling of arms and legs, whereby arm movements can support leg movements. One side of the body can also partially compensate for the weakness of the other side, as the movement patterns are linked. However, this method does not focus on differentiated control of residual muscle power or a classic assistance-as-needed principle. Rather, it requires active participation, sufficient core stability and cognitive abilities for movement control.

Functionally, RST is therefore limited to people who can actively participate. In cases of severe paresis, reduced trunk stability or limited cognitive performance, it is often not possible to perform the exercise in a meaningful way, as both the coordinated use of arms and legs and conscious movement control are required to carry out effective training that goes beyond basic mobilisation.

Despite specific advantages in its application, there are currently no randomised controlled studies that prove the functional or everyday relevance of RST compared to CL. In particular, with regard to early mobilisation, adaptability for severely impaired individuals and evidence-based effectiveness, there is currently no clear advantage in favour of RST.

Further potential arises from combining CL with supportive processes: In a controlled study, co-treatment using functional electrical stimulation (FES) delivered additional improvements in trunk control and walking distance (Aaron et al., 2018). Multimodal approaches like these expand the potential applications, especially for patients with severe paralysis or central motor inactivity.

CL is also becoming increasingly established in intensive care settings with a strong evidence base. A recent review showed that in-bed cycling can improve the functional outcome of critically ill patients in intensive care and shorten the length of stay in intensive care units (O’Grady et al. 2024). These findings were incorporated into the updated US guideline on early mobilisation in 2025, which explicitly recommends “enhanced mobilization” – including in-bed cycling after ICU admission (Critical Care Society, 2025).

CL is an adaptive, evidence-based and versatile training method across the entire care continuum – from intensive care to post-acute rehabilitation.

In contrast to the even distribution of force in the rotational cycle during CL, the linear movement during RST can lead to increased stress on individual muscle groups – especially the knee extensors – particularly at higher resistances or with limited joint mechanics. Functional-structural limitations such as arthritis or obesity may potentially reduce movement tolerance under these conditions.

From a neurophysiological perspective, the rhythmic-symmetrical leg movement during CL has an activating effect on spinal central pattern generators (CPGs) and supports the functional reorganisation of cortico-spinal networks through sensorimotor feedback (Klarner et al. 2014). This effect can be further enhanced through forced-rate protocols – deliberately increased pedalling frequencies. A randomised controlled study documented significant improvements in both Fugl-Meyer motor function and VO₂ peak in stroke patients after eight weeks of high-frequency CL training (Linder et al., 2024).

Even with RST, CPG activation is fundamentally possible, provided the movement is rhythmic, bilateral and repetitive. However, corresponding evidence has not yet been comprehensively documented. Overall, the biomechanical and neurophysiological characteristics particularly support the versatile and early possible use of CL in neurological and geriatric rehabilitation.

A typical RST device with dimensions of approximately 1.85 m × 0.76 m requires nearly twice the floor space of a CL system (approx. 0.90 m × 0.57 m) and weighs around 129 kg, which is approximately three times the weight. This not only hampers flexible use across various therapy settings, but also constrains the device’s mobility, particularly when space requirements change or therapy units undergo reorganisation. RST systems are exclusively for stationary use; patient transfer to the device seat is necessary and typically requires assistance from one or two caregivers when dealing with higher care needs.

Cycle ergometers, by contrast, are typically wheelchair accessible, mounted on mobile platforms, and specifically designed to be used even by those with severely limited muscle function (grade 0 or 1). Thanks to integrated passive and assistive modes, therapeutic use is possible even when patients cannot yet fully participate actively – such as during early stroke recovery or for severely compromised geriatric patients.

Looking at the economic benefits, the integration of CL systems presents a clear advantage. Modern CL systems typically combine three key functions in a single device: passive mobilisation, assistive training and active ergometer load. This reduces the need for separate individual devices, lowers acquisition and maintenance costs, and simplifies staff training. With its lower technical complexity, reduced space requirements and versatility in day-to-day therapy, CL stands out as a highly efficient training method – not just clinically, but logistically and economically as well.

By comparison, CL offers a much wider range of therapeutic applications, ranging from passive early mobilisation on the intensive care unit to assistive-symmetrical motor relearning for severe hemiparesis to active high-intensity training protocols for secondary prevention. This adaptability is greatly enhanced through motor-assisted movement capabilities and standardised ergometry modules that precisely control the training parameters. The evidence base is comprehensive, spanning from mechanistic studies on muscle activation and neuroplastic reorganisation to randomised controlled trials, meta-analyses and current guideline recommendations. In particular, the integration of CL into early mobilisation protocols in intensive care units, alongside neurorehabilitative and geriatric care standards, highlights the significant clinical value of this training approach.

- Aaron SE, Vanderwerker CJ, Embry AE, Newton JH, Lee SCK, Gregory CM. FES-assisted Cycling Improves Aerobic Capacity and Locomotor Function Postcerebrovascular Accident. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Mar;50(3):400-406. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001457. PMID: 29461462; PMCID: PMC5847329.

- Barclay A, Gray S, Paul L, Rooney S. (2022). The effects of cycling using lower limb active passive trainers in people with neurological conditions: a systematic review. International Journal of Therapy And Rehabilitation. 29. 1-21. 10.12968/ijtr.2020.0171.

- Billinger SA, Tseng BY, Kluding PM. Modified total-body recumbent stepper exercise test for assessing peak oxygen consumption in people with chronic stroke. Phys Ther. 2008 Oct;88(10):1188-95. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080072. Epub 2008 Sep 4. PMID: 18772275; PMCID: PMC2557055.

- Klarner T, Barss TS, Sun Y, Kaupp C, Zehr EP. Preservation of common rhythmic locomotor control despite weakened supraspinal regulation after stroke. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014 Dec 22;8:95. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00095. PMID: 25565995; PMCID: PMC4273616.

- Kutzner I, Heinlein B, Graichen F, Bender A, Rohlmann A, Halder A, Beier A, Bergmann G. Loading of the knee joint during activities of daily living measured in vivo in five subjects. J Biomech. 2010 Aug 10;43(11):2164-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.046. PMID: 20537336.

- Linder SM, Lee J, Bethoux F, Persson D, Bischof-Bockbrader A, Davidson S, Li Y, Lapin B, Roberts J, Troha A, Maag L, Singh T, Alberts JL. An 8-week Forced-rate Aerobic Cycling Program Improves Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Persons With Chronic Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2024 May;105(5):835-842. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2024.01.018. Epub 2024 Feb 11. PMID: 38350494; PMCID: PMC11069437.

- O’Grady HK, Hasan H, Rochwerg B, Cook DJ, Takaoka A, Utgikar R, Reid JC, Kho ME. Leg Cycle Ergometry in Critically Ill Patients - An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. NEJM Evid. 2024 Dec;3(12):EVIDoa2400194. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2400194. Epub 2024 Oct 9. PMID: 39382351.

- Tiebel, Jakob. (2018). Cycling for walking after stroke. 10.6084/m9.figshare.6016043.

- Veldema J, Jansen P. Ergometer Training in Stroke Rehabilitation: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 Apr;101(4):674-689. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.09.017. Epub 2019 Nov 2. PMID: 31689416.

Related contents

Find related exciting contents in our media library.

Meet our specialists.

Are you interested in our solutions? Schedule a meeting with a Consultant to talk through your strategy and understand how TEHRA-Trainer can help you to advance rehabilitation.

You need to load content from reCAPTCHA to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Turnstile. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information