THERAPY-Magazin

How strenuous should it be?

Stroke patients benefit from guided self-training. Learn how the Borg scale helps manage exercise intensity and improves endurance, mobility, and independence.

Jakob Tiebel

Health Business Consultant

After a stroke, self-training with a movement therapy device has been proven to help ensure that treatment is successful. However, therapists are often at a loss when it comes to making recommendations for training management, meaning that patients are often left to work their training out for themselves. The Borg scale, a reliable indicator with which therapists can record and assess the subjective exertion during training, can remedy this.

Self-training managed by the patients is essential to outpatient aftercare in order to maintain the progress achieved in the context of stationary rehabilitation and to continue to improve motor skills and physical fitness after a stroke [1].

In this context, the use of a power-operated movement exerciser has proven to be a useful extension of physiotherapy and ergotherapy. Intensive and regular training improves the ability to walk and general endurance, and increases independence in various everyday situations [2-4].

Self-training and regular checking of this therefore play an extremely important role in the outpatient setting as the therapy dosage is a crucial factor for success. The provision of outpatient medical care alone is no guarantee of the training intensity, duration and frequency required for motor learning. However, if patients use part of their time when not in treatment to independently train with the device, they can actively support the success of the treatment. In addition, they learn to take responsibility for themselves and their own situation and can experience their own self-efficacy [1,6].

Generally speaking, patients are able to carry out training of their own accord at home and without much difficulty after some practice.

A movement exerciser soon proves to be suitable thanks to its construction, its simple and intuitive operation, and the high level of safety during training. It is a type of modified bicycle ergometer with a motor drive, with which patients who cannot walk or whose ability to walk is heavily impaired can perform repetitive arm and leg movements from their wheelchair or a chair. Here, the brake resistance can be precisely controlled and adjusted to the individual performance levels of the patient.

However, it is essential to successful self-training that patients learn from the outset how to use the equipment correctly and how to adequately manage and pace their training. Sadly, however, the networking and interdisciplinary cooperation required for this between providers, therapists and patients is something of a pipe-dream in the outpatient sector. A lack of communication and specialist knowledge, time constraints and a lack of clarity regarding the remuneration situation stand in the way of interdisciplinary coordination [5]. Patients who have received a movement exerciser for training at home are often only briefly trained in operating the device upon delivery and are then left to fend for themselves [3]. Although the patients often make subsequent enquiries into how to train correctly, they only rarely receive sufficiently useful information.

It is certainly no easy task to find the suitable intensity for adapted training and to correctly assess effort. It is often difficult to give a clear training recommendation, particularly to older persons or patients with cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal conditions. Comprehensive endurance tests to determine physiological parameters (VO2 max, blood lactate) would be necessary but are far too complex and not at all feasible in an outpatient setting [6].

By contrast, a very simple yet precise option for identifying the perceived exertion of individuals and establishing the level of effort in training is the Borg scale, which was developed in 1970 by Swedish scientist Gunnar Borg. This 15-point scale is easy to apply and the patients themselves are capable of understanding it and using it to manage their training [6].

This type of assessment is widespread in neurological rehabilitation. It is often implemented in training studies for performance diagnostics and resistance control [6]. Kamps and Schüle, along with Dobke et al., were able to prove in 2005 and 2010 that the Borg scale works equally well for managing the physical exercise of stroke patients living at home. Firstly, they established the exertion for the training according to Borg, then compared the training-specific results with the results of a six-minute walking test and came to the conclusion that the exertion during training actually corresponded to general endurance in everyday situations. In addition, they established that regularly checking the performance level using the Borg scale was highly motivational for patients. Reaching a greater pedalling resistance was important to patients and provided them with an incentive to exercise, which resulted in them significantly increasing their performance during the course of training [3,4].

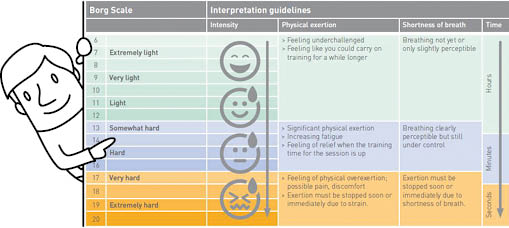

It is extremely simple to work with the assessment. Using the classic Borg scale, or “ratings of perceived exertion” (RPE), the patient’s subjective perceived exertion during or directly after the training session was quantified. The 15-point intervals scale is divided into numerical values from 6 to 20. The odd numerical values are additionally provided with interpretive descriptions (from 7 = “Extremely light” to 19 = “Extremely hard”) to ensure the linearity of the scale [6].

Depending on the performance level of the patients, the aim is to train at the sub-maximal level over a time period of around 15-20 minutes. A session always consists of warm-up and warm-down phases of two to three minutes, with the active walking phase between them. The brake resistance of the device has to be set up so that the exertion corresponds with level 13 (“somewhat hard”), which amounts to moderate endurance training from a scientific training research perspective [3,4].

Those who want to be more precise should determine the maximum performance in an initial test in order to then be able to establish the values for endurance training as accurately as possible. When identifying the training parameters for the sub-maximal performance level, the variation is generally larger. Following the initial test, the patients can then manage the training themselves using the scale and simultaneously use the values as a reference for reproducing the level of exertion in everyday situations [6].

For validity, it must be said in summary that all standard physiological criteria (heart rate, blood lactate, VO2 max %, VO2 %, breathing rate and ventilation) correlate equally strongly with the RPE scale. For practical reasons, however, the breathing rate is the best indicator of the degree of physical exertion [6].

In this context, the use of a power-operated movement exerciser has proven to be a useful extension of physiotherapy and ergotherapy. Intensive and regular training improves the ability to walk and general endurance, and increases independence in various everyday situations [2-4].

Self-training and regular checking of this therefore play an extremely important role in the outpatient setting as the therapy dosage is a crucial factor for success. The provision of outpatient medical care alone is no guarantee of the training intensity, duration and frequency required for motor learning. However, if patients use part of their time when not in treatment to independently train with the device, they can actively support the success of the treatment. In addition, they learn to take responsibility for themselves and their own situation and can experience their own self-efficacy [1,6].

Generally speaking, patients are able to carry out training of their own accord at home and without much difficulty after some practice.

A movement exerciser soon proves to be suitable thanks to its construction, its simple and intuitive operation, and the high level of safety during training. It is a type of modified bicycle ergometer with a motor drive, with which patients who cannot walk or whose ability to walk is heavily impaired can perform repetitive arm and leg movements from their wheelchair or a chair. Here, the brake resistance can be precisely controlled and adjusted to the individual performance levels of the patient.

However, it is essential to successful self-training that patients learn from the outset how to use the equipment correctly and how to adequately manage and pace their training. Sadly, however, the networking and interdisciplinary cooperation required for this between providers, therapists and patients is something of a pipe-dream in the outpatient sector. A lack of communication and specialist knowledge, time constraints and a lack of clarity regarding the remuneration situation stand in the way of interdisciplinary coordination [5]. Patients who have received a movement exerciser for training at home are often only briefly trained in operating the device upon delivery and are then left to fend for themselves [3]. Although the patients often make subsequent enquiries into how to train correctly, they only rarely receive sufficiently useful information.

It is certainly no easy task to find the suitable intensity for adapted training and to correctly assess effort. It is often difficult to give a clear training recommendation, particularly to older persons or patients with cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal conditions. Comprehensive endurance tests to determine physiological parameters (VO2 max, blood lactate) would be necessary but are far too complex and not at all feasible in an outpatient setting [6].

By contrast, a very simple yet precise option for identifying the perceived exertion of individuals and establishing the level of effort in training is the Borg scale, which was developed in 1970 by Swedish scientist Gunnar Borg. This 15-point scale is easy to apply and the patients themselves are capable of understanding it and using it to manage their training [6].

This type of assessment is widespread in neurological rehabilitation. It is often implemented in training studies for performance diagnostics and resistance control [6]. Kamps and Schüle, along with Dobke et al., were able to prove in 2005 and 2010 that the Borg scale works equally well for managing the physical exercise of stroke patients living at home. Firstly, they established the exertion for the training according to Borg, then compared the training-specific results with the results of a six-minute walking test and came to the conclusion that the exertion during training actually corresponded to general endurance in everyday situations. In addition, they established that regularly checking the performance level using the Borg scale was highly motivational for patients. Reaching a greater pedalling resistance was important to patients and provided them with an incentive to exercise, which resulted in them significantly increasing their performance during the course of training [3,4].

It is extremely simple to work with the assessment. Using the classic Borg scale, or “ratings of perceived exertion” (RPE), the patient’s subjective perceived exertion during or directly after the training session was quantified. The 15-point intervals scale is divided into numerical values from 6 to 20. The odd numerical values are additionally provided with interpretive descriptions (from 7 = “Extremely light” to 19 = “Extremely hard”) to ensure the linearity of the scale [6].

Depending on the performance level of the patients, the aim is to train at the sub-maximal level over a time period of around 15-20 minutes. A session always consists of warm-up and warm-down phases of two to three minutes, with the active walking phase between them. The brake resistance of the device has to be set up so that the exertion corresponds with level 13 (“somewhat hard”), which amounts to moderate endurance training from a scientific training research perspective [3,4].

Those who want to be more precise should determine the maximum performance in an initial test in order to then be able to establish the values for endurance training as accurately as possible. When identifying the training parameters for the sub-maximal performance level, the variation is generally larger. Following the initial test, the patients can then manage the training themselves using the scale and simultaneously use the values as a reference for reproducing the level of exertion in everyday situations [6].

For validity, it must be said in summary that all standard physiological criteria (heart rate, blood lactate, VO2 max %, VO2 %, breathing rate and ventilation) correlate equally strongly with the RPE scale. For practical reasons, however, the breathing rate is the best indicator of the degree of physical exertion [6].

2017-2

Audience

Inpatient Rehabilitation

Knowledge

Long Term Care

Outpatient Rehabilitation

Section

Therapy & Practice

THERAPY Magazine

Jakob Tiebel

Health Business Consultant

Jakob Tiebel is OT and studied applied psychology with a focus on health economics. He has clinical expertise from his previous therapeutic work in neurorehabilitation. He conducts research and publishes on the theory-practice transfer in neurorehabilitation and is the owner of an agency for digital health marketing.

References:

- Lamprecht H. Ambulante Neuroreha nach Schlaganfall – ein Plädoyer für Intensivprogramme. Physiopraxis 2016; 14(9): 13-15

- Podubecka J, Scheerl S, Theilig S, Wiederer R, Oberhoffer R, Nowak DA. Cyclic Movement Training versus Conventional Physiotherapy for Rehabilitation of Hemiparetic Gait after Stroke: A Pilot Study. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2011; 79(7): 411-418

- Kamps A, Schüle K. Cyclic movement training of the lower limb in stroke rehabilitation. Neurol Rehabil 2005; 11 (5): 259 – 269

- Dobke B, Schüle K, Kaiser T. Use of an assistive movement training apparatus in the rehabilitation of stroke patients. Neurol Rehabil 2010; 16 (4): 173 – 185

- Driemel C, Schittenhelm A. Hilfsmittelversorgung. Eine Herausforderung - auch für uns Physiotherapeuten. pt_Zeitschrift für Physiotherapeuten 2015; 67(4): 65-67

- Schefer M. Wie anstrengend ist das für Sie? Assessment: Borg-Skala. Physiopraxis 2008

Related contents

Find related exciting contents in our media library.

Mehr laden

This is not what you are searching for? Knowledge

Meet our specialists.

Are you interested in our solutions? Schedule a meeting with a Consultant to talk through your strategy and understand how TEHRA-Trainer can help you to advance rehabilitation.