Discover how customized motor therapy helps MS patients improve strength, endurance, and walking ability. Learn about the role of interval training and THERA-Trainer devices in treating paresis and boosting mobility.

MS is the most common neurological disorder in young adults and the most common cause of disability for young people. The disease peak is just 25 years old. New insights into the clinical picture make physiotherapy and occupational therapy even more important than before. These days, improved diagnostics mean that the disease can be diagnosed very early on, often after the first neurological symptom. The diagnostic procedure consists of a clinical examination of the symptoms, an examination of the evoked potentials (i.e. measurement of the central nerve conduction velocity) and if necessary a CSF examination.

In recent years, not only has diagnosis improved, but a lot has also been done in causal MS therapy in terms of medication. Nevertheless, the following still applies: The earlier the diagnosis is made and causal drug therapy is started, the better the success of therapies. The variety of therapies is very broad and targeted medical intervention is possible, especially with relapsing-remitting MS, while causal medication often struggles to counter the often creeping chronic deterioration.

Therapy is essential at every stage of MS. Time and again it is shown that with targeted physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and certainly speech therapy, great success can be achieved. The effectiveness of weight training [3], balance training [5,6], training on movement exercisers [1] and treadmill training [10, 12] is just as proven for MS patients as the effectiveness of group therapies [11].

MS has its own pathophysiology, which differs from other neurological diseases. This requires a disease and symptom-specific approach to motor MS therapy. The very different progression of the disease, the wide range of symptoms and not least the necessary interdisciplinary approach make treating MS a major challenge.

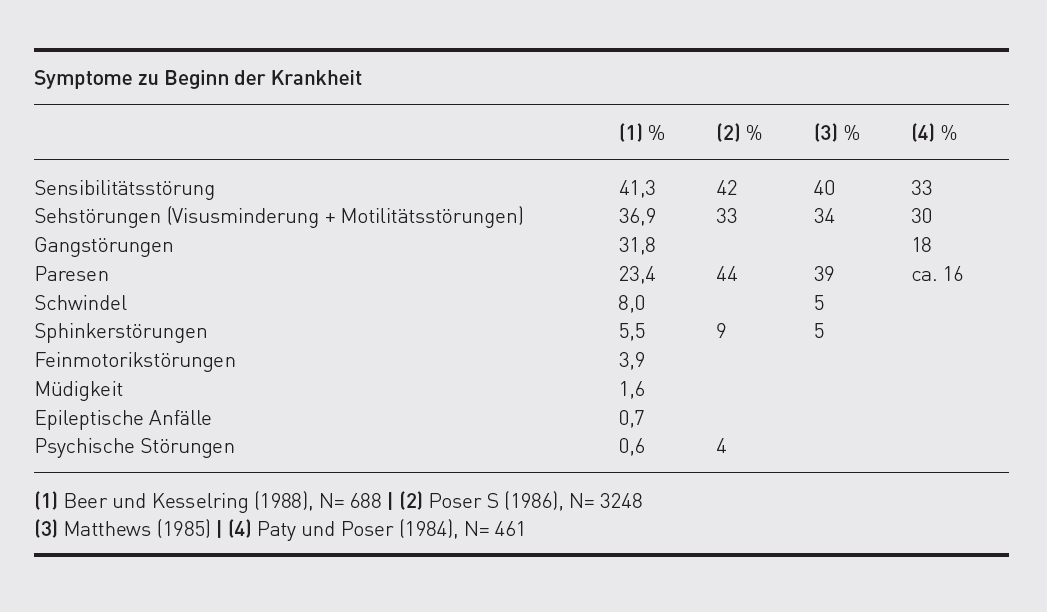

The disease often begins in episodes, with the patient affected by only one or a wide range of symptoms. Initial episodes often present themselves as visual and somatosensory disorders or muscle weaknesses.

After an initial episode, the symptoms can completely regress and sufferers can go years without any problems. [Kesselring 2010]. Irregular episodes usually pass into what is known as secondary progressive MS after years and develop into a gradual worsening of the symptoms. The main motor symptoms of MS are:

- Paresis/weaknesses

- Motor and cognitive fatigue

- Spasticity – usually combined with paresis

- Ataxia – often combined with cognitive symptoms

In addition, somatosensory disorders, bladder problems, cognitive deficits and mental health problems (especially depression) often occur. [7]

According to one study, paresis is an early symptom of MS in up to 44 percent of patients. It is therefore more common than somatosensory disorders (about 42 percent) and the most disabling symptom in terms of function. As the disease progresses, paresis is usually associated with compensatory spasticity and thus often leads to therapists and doctors being more likely to focus on spasticity. Therapists are able to proceed effectively and specifically against weakness and achieve good functional improvements.

At the onset of the disease, the dorsal flexors are primarily affected, later hip flexors and abdominal muscles are impacted; weaknesses in the quadriceps muscle and the calf muscles are also frequently found and are especially noticeable when walking [9]. This functional chain leads to a common MS-specific problem while walking.

MS patients often say they stumble when walking and their toes get stuck. Particularly weak muscles react in the short term with a significant deterioration in their strength and endurance performance. In contrast to stroke patients, MS patients usually demonstrate no circumduction, as the calf is less spastic and therefore the foot is not so heavily plantarflexed. Since a weakness in foot dorsiflexion cannot be compensated for by increased leg lift, many MS patients complain of difficulties in bringing the leg forward while walking; it "sticks" to the floor. This is illustrated in a gait analysis, where sufferers have difficulty with the non-supporting leg phase and use a stick on the weaker side to bring the affected leg forward.

Fatally, combined with an increase in reflex activity, this often leads doctors to conclude that the reason for the problems is too high a tone (= spasticity). Paresis is therefore not looked into and, in the worst case, antispasmodics are prescribed which make paresis worse.

Dorsal flexors are not strength muscles, but must work constantly when walking. We therefore need to look at the power of the muscles in connection with their function. Because endurance is severely impaired by motor fatigue with MS, it is recommended to first tire out the dorsal flexors in addition to a standard muscle function test, and then test them again. In practice, this has involved knocking the forefoot on the ground with about twenty repetitions and then another strength test.

We then see the typical weaknesses that would not be found with a single test. This strength endurance deficit causes patients to avoid longer stretches of walking at the beginning of the illness, which in turn further worsens endurance performance. This vicious cycle can be broken by consistently using interval training for walking distances and specifically strengthening the affected muscles in parallel.

The evidence of weight training for MS is well established in studies [2,3,4]. The dorsal flexor can be trained by repeatedly tapping the forefoot on the floor (effective therapy intensity from about 100 repetitions per day). Furthermore, the dorsal flexor is activated, especially when functionally walking uphill.

The more frequently used dorsal flexor systems with functional electrostimulation are also certainly a very effective aid for MS. It is important that the device is light, so that the patient is not forced to carry extra weight with each step.

Every step – including walking with appropriate aids – functionally activates and strengthens the crucial muscle chains, including the torso.

The slower a person walks, the more balance and strength they need. Because MS patients have a much slower pace compared to healthy individuals, they need more activity and strength in their hip flexors. However, these flexors often show early signs of weaknesses as well and therefore also need to be trained for endurance. Here too, targeted strength training of the hip flexor and the entire ventral chain helps, whether with traction devices, Thera bands or by walking uphill, climbing stairs, etc.

The quadriceps muscle must be able to hold our entire body weight on one leg while walking. A weakness in the quadriceps is often compensated for by hyperextension in the knee. Its functional activity should be tested, for example, with knee bends on one leg with a straight upper body, and then it needs to be trained for strength with an effective training stimulus. The goal is for the patient to repeatedly support their body weight on one leg. If the leg axis cannot be maintained, it is advisable to repetitively train individual movement sections on the climbing wall. Here we mean pushing up the body weight and eccentric easing with one leg.

The calf muscles should also be strengthened, as the calf on each leg must bring the entire body weight forward as quickly as possible. Here, training needs to focus on strength and elasticity. The calf muscles can be tested by checking that the patient is capable of standing on tip toes on one leg. Again, both test and training must focus on frequent repetitions. The patient can work on their strength endurance and elasticity by jumping, skipping or standing on tip toes on one leg.

The upper limbs are usually less affected in MS patients. In the advanced stages of the disease, however, arm/hand paresis can occur. The tone increase is very moderate in the upper limbs. Here, too, paresis is the most common functional problem besides somatosensory disorders. The small hand muscles in particular are often weak very early on, which is reflected in problems with fine motor skills. This can be counteracted with daily training involving repetitive endurance exercises and strength exercises, such as frequent training with heavy Baoding balls or clothes pegs. In addition, proximal muscle weaknesses and shoulder muscle weaknesses are possible, which often result from a weakness of the rotator cuff in MS patients, which leads to insufficient guidance of the humeral head. Therefore, it is important to train the shoulder muscles in closed chains, as is the case with all support activities and many training devices.

Training with an active-passive movement exerciser such as the THERA-Trainer tigo specifically works the dorsal flexor, hip flexor and quadriceps with the active pedalling of both legs, and is therefore specific, meaningful training for people with MS in all stages of the disease, not only for contracture prophylaxis and reduced spasticity.

Appropriate resistances must be set in order to train weak muscles. To improve endurance, the patient must walk until they have muscular fatigue and then, after short breaks (often three to five minutes is enough) continue with the training process, as interval training. Here the emphasis is on strength endurance training.

The most important qualities of walking are endurance and speed. While walking endurance is improved by targeted interval training, speed should be specifically targeted with speed training on treadmills, for example. If there is no treadmill, patients should repeatedly walk short distances as fast as possible. If a gait trainer like the THERA-Trainer e-go is available, they can also practise walking on the floor.

Auch zum Training der proximalen Kraftausdauer und damit auch der Schulter- und Anbindung an die Rumpfmuskulatur bietet sich ein regelmäßiges Training mit dem THERA-Trainer tigo an. Ein Vorteil des Trainings mit dem THERA-Trainer tigo ist, dass der Trainingsreiz zu Hause genügend hoch und häufig angesetzt werden kann, da es durchaus sinnvoll ist, täglich oder besser dreimal täglich zu trainieren. Je geringer die Ausdauer pro Trainingseinheit ist, desto häufiger sollte mit geringem Trainingsreiz trainiert werden.

Paresis is functionally the most debilitating symptom for people with MS. In combination with exertional motor fatigue and the Uhthoff phenomenon, it is the cause of a widespread error in treatment: both MS sufferers and many therapists want to avoid exertion – and rest when action is urgently needed. However, this rest often means a steady decline in functions for those affected by MS. If they actively train at all, then usually it is with too little training stimulus and no long-term training development plan. However, training can restore lost functions and lead to amazing functional improvements in strength, endurance and balance. [8]

The implications for therapy are that MS patients should train specifically and permanently with an effective training stimulus and a high number of repetitions, and should not be afraid of overdoing it. Effort does not trigger episodes – a temporary worsening of symptoms is a sign of MS-specific pathophysiology and no reason to reduce regular training!

Since MS patients are often still young, the cardiovascular issue is less of a concern.

- Corrales Mora C: Apparativ-assistives Training mit Multiple Sklerose Patienten. Diplomarbeit 2002, Deutsche Sporthochschule.

- Dalgas U, Ingemann-Hansen T, Stenager E: Physical Exercise and MS – Recommendations: The International MS Journals, 2009; 16: 5-11.

- Dalgas U, Kant M, Stenager E: Resistance Training in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis; Akt Neurol 2010; 37(5): 2013-2018

- Filipi EO, Ridpath AC, Leuschen MP: Improvement in strength following resistance training in MS patients despite varied disability levels. Neuro Rehabilitation 2011; 28: 373-382

- Fjeldstad C et al.: Decreased postural balance in multiple sclerosis patients with low disability. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2010, Jul 31.

- Freeman JA et al.: The effect of core stability training on balance and mobility inambulant individuals with multiple sclerosis: a multi-centre series of single casestudies. Multiple Sclerosis 2010 Nov; 16(11)

- Kesselring J: Multiple Sklerose, 4. Auflage, Kohlhammer Verlag, 2004.

- Lamprecht S, Dettmers Ch: Sport bei schwer betroffenen Patienten mit Multipler Sklerose; Neruol Rehabil 2013; 19(4): 244-246.

- Lamprecht S: NeuroReha bei Multipler Sklerose Physiotherapie – Sport – Selbsthilfe, Thieme Verlag, 2008.

- Laufens G, Poltz W, Prinz E, Reimann G, Schmiegelt F: Verbesserung der Lokomotion durch kombinierte Laufband-/Vojta-Physiotherapie bei ausgewählten MS-Patienten, Phys Rehab Kur Med 9 (1999), 187-189.

- Tarakci E, Yeldan I, Huseyinsinoglu BE, Zenginler Y, Eraksoy M: Group exercise training for balance, functional status, spasticity fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial; Clin Rehabil, 2013 Sep; 27(9): 813-22

- Van den Berg et al. 2006

Related contents

Find related exciting contents in our media library.

Meet our specialists.

Are you interested in our solutions? Schedule a meeting with a Consultant to talk through your strategy and understand how TEHRA-Trainer can help you to advance rehabilitation.

You need to load content from reCAPTCHA to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Turnstile. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information