THERAPY-Magazin

The neurological patient

Helmut Krause

CEO AMBUTHERA

If you ask patients, on the day they are admitted to hospital,

what their goals are, they generally reply:

"I want to be able to walk again!"

Free and independent walking appears to be top priority.

what their goals are, they generally reply:

"I want to be able to walk again!"

Free and independent walking appears to be top priority.

We know that three months after a stroke, around 70% of patients have regained the ability to walk. But we also know that only around 7% of these patients can walk 500 metres in one go following their stay on a rehabilitation ward. Moreover, their speed of walking often remains considerably reduced. Patients are not quick enough to be able to cross the road safely.

Firstly, let’s review the path our patients take from the day of the incident to the day they are discharged from the rehabilitation unit. Depending on the severity of the symptoms, acute medical care is the initial focus of attention.

Firstly, let’s review the path our patients take from the day of the incident to the day they are discharged from the rehabilitation unit. Depending on the severity of the symptoms, acute medical care is the initial focus of attention.

"How can we improve things?"

This phase of the rehabilitation process can be described as a “phase of purposelessness”. It generally leads to a complete loss of independence. Those affected are suddenly torn from their usual way of life and are usually completely helpless and dependent. They have to put responsibility for themselves and their life – often unwillingly – into the hands of physicians and therapists.

Once their condition has stabilised, the first “intentions” are formed. Many patients are relieved that they are still alive. A search for orientation begins. It is generally during this phase that the patient is admitted into a rehabilitation unit. By this time, the goal should be that patients move away from the role of being the “treated person” and again start to take responsibility for themselves and the rehabilitation process. Ultimately, goal-oriented rehabilitation should not only restore maximum independence, but should also motivate the patient to continue to work on their individual goals after the rehabilitation process and to maintain and improve their condition. For this to happen, patients need to move as early as possible back into the role of “actor”.

Patient and therapist work closely together and there is a clear division of tasks. The patient formulates the goal and the therapist maps out the right path. This kind of collaboration can be illustrated by the image of a mountain guide and his companion. The guide shows the hiker the path to the summit, but the hiker has to walk and carry his own backpack. Often, it is a long and, in parts, very demanding path. For that reason, motivation is a vital factor in long-term rehabilitation. Above all, the motivation to work independently on the defined objectives well beyond regular therapy.

Once their condition has stabilised, the first “intentions” are formed. Many patients are relieved that they are still alive. A search for orientation begins. It is generally during this phase that the patient is admitted into a rehabilitation unit. By this time, the goal should be that patients move away from the role of being the “treated person” and again start to take responsibility for themselves and the rehabilitation process. Ultimately, goal-oriented rehabilitation should not only restore maximum independence, but should also motivate the patient to continue to work on their individual goals after the rehabilitation process and to maintain and improve their condition. For this to happen, patients need to move as early as possible back into the role of “actor”.

Patient and therapist work closely together and there is a clear division of tasks. The patient formulates the goal and the therapist maps out the right path. This kind of collaboration can be illustrated by the image of a mountain guide and his companion. The guide shows the hiker the path to the summit, but the hiker has to walk and carry his own backpack. Often, it is a long and, in parts, very demanding path. For that reason, motivation is a vital factor in long-term rehabilitation. Above all, the motivation to work independently on the defined objectives well beyond regular therapy.

“Linking up to a computer means that training today can be very clearly defined. Patients get direct feedback on performing the movement and are motivated to improve their condition through active exercise.”

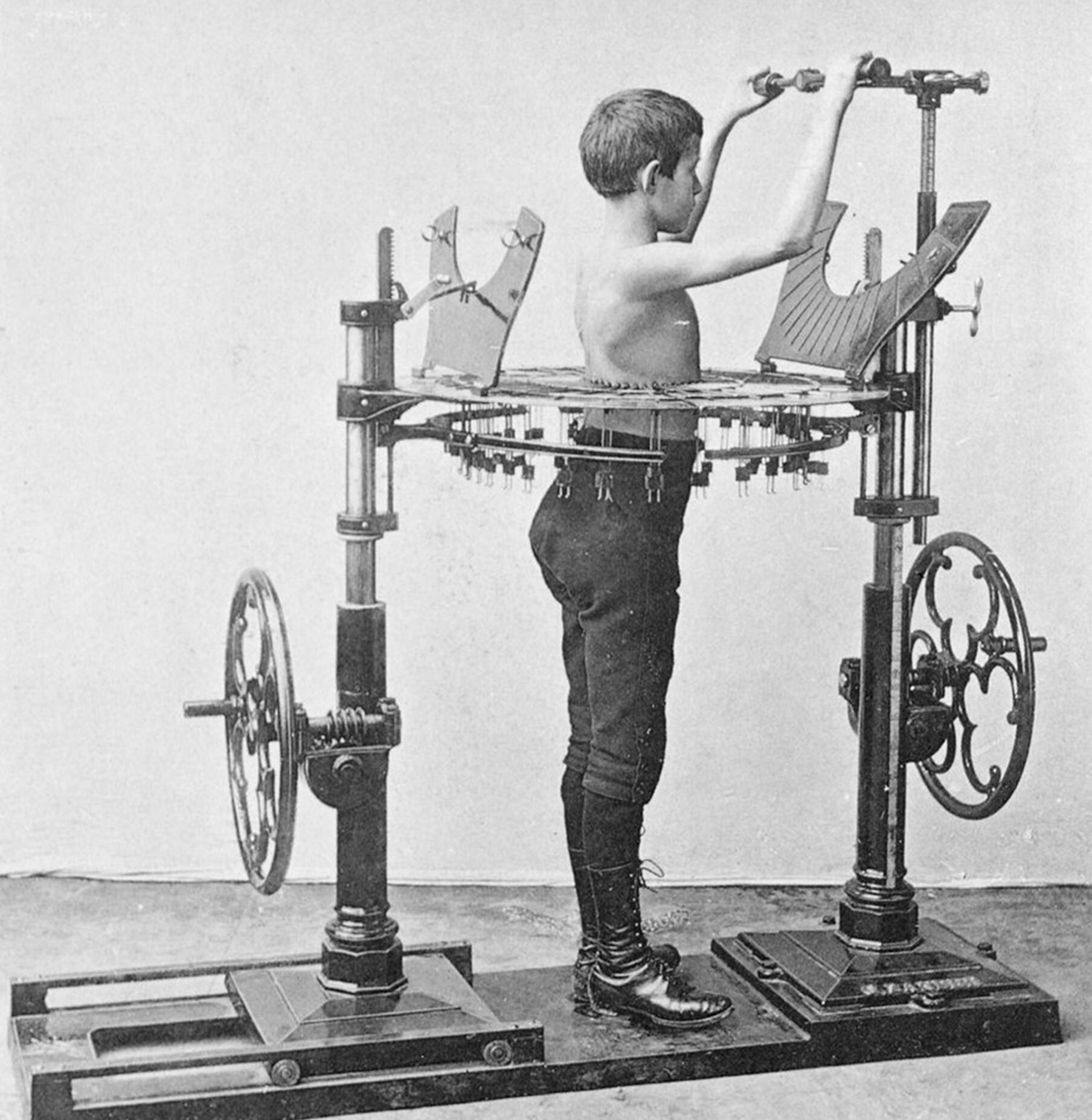

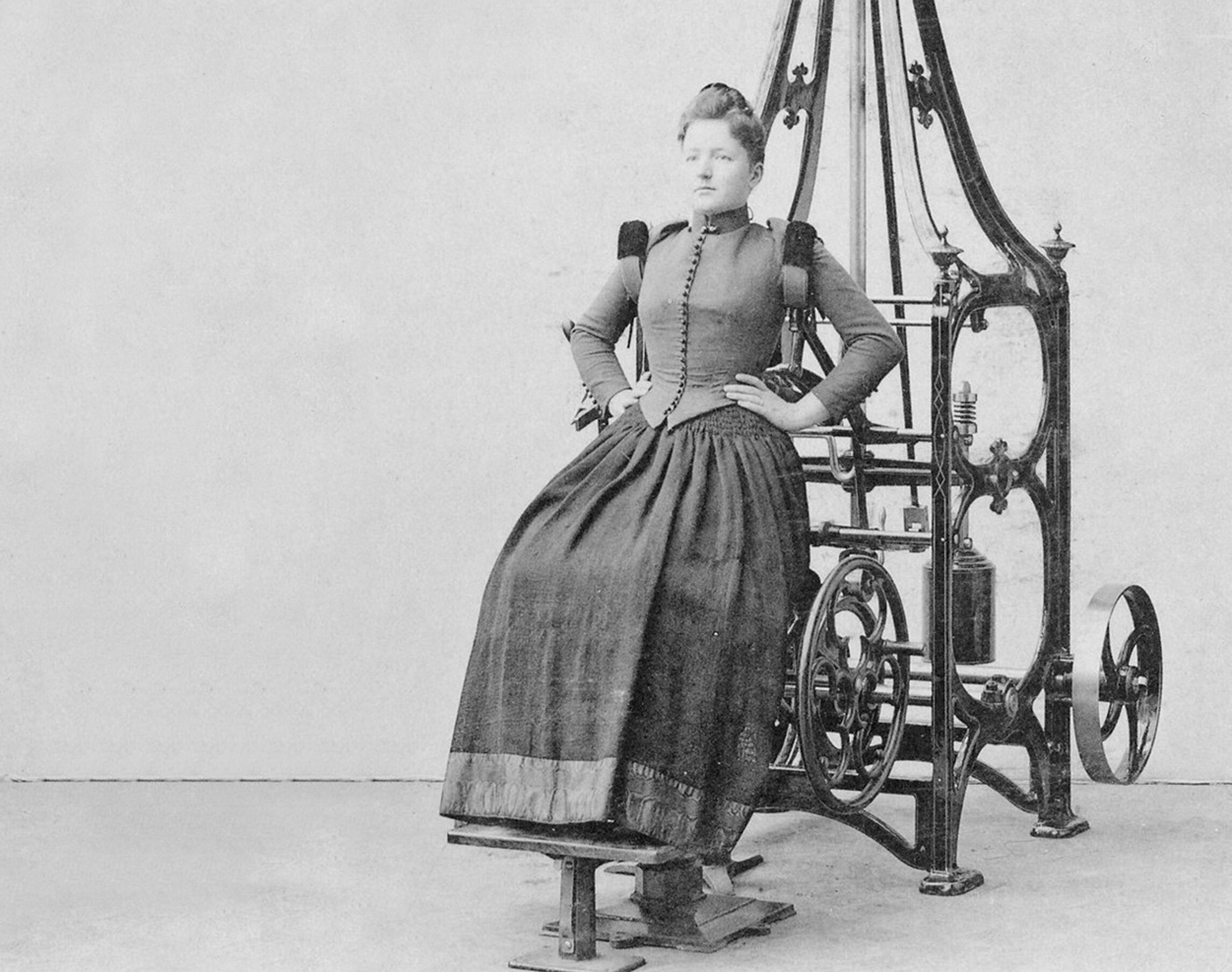

Towards the end of the 19th century, the early principles of motor learning were already being described by the Swedish physician and physiotherapist Jonas Gustav Vilhelm Zander, and “medico-mechanical devices” were even being used for effective therapeutic gymnastics. Zander pursued this line of thinking because “you only learn what you practise […] through frequent repetition of exercise sequences”.

Today, this thinking is perhaps more current than ever in modern rehabilitation. With the continuous development of different therapy devices and the use of technologies, patients can be offered more differentiated therapies adapted to their individual needs and capabilities. The benefits are clear: Without any additional expense, therapy frequency can be significantly increased for the patient and the motivation to train is boosted.

What does this mean for therapy? Our sector has been in a sustained process of change for some years now, moving away from traditional methods and towards evidence-based practice. In these phases, too, new intentions are formed, new courses of action initiated, maintained and critically examined on a continuous basis. So go with it!

Today, this thinking is perhaps more current than ever in modern rehabilitation. With the continuous development of different therapy devices and the use of technologies, patients can be offered more differentiated therapies adapted to their individual needs and capabilities. The benefits are clear: Without any additional expense, therapy frequency can be significantly increased for the patient and the motivation to train is boosted.

What does this mean for therapy? Our sector has been in a sustained process of change for some years now, moving away from traditional methods and towards evidence-based practice. In these phases, too, new intentions are formed, new courses of action initiated, maintained and critically examined on a continuous basis. So go with it!

Ambulante Rehabilitation

Fachkreise

Stationäre Rehabilitation

Helmut Krause

CEO AMBUTHERA

Helmut Krause earned his degree as a certified occupational therapist at DIPLOMA in Nordhessen, Germany. As an occupational therapist, he worked for several years in neurology and early rehabilitation. From 2002 to 2004, he was the Head of Occupational Therapy at the Neurological Therapy Center in Cologne before moving to St. Mauritius Therapy Clinic in Meerbusch in 2005. Until 2015, he served as the Head of Motor Skills at St. Mauritius Therapy Clinic in Meerbusch. Helmut Krause has since founded his independent consulting firm, 'AMBUTHERA,' where he successfully advises clinics and therapy centers as well as medium-sized companies in the medical technology sector. Lectures on modular therapy and gait rehabilitation are among Helmut Krause's specialties.

References:

Related contents

Find related exciting contents in our media library.

This is not what you are searching for? Knowledge

Meet our specialists.

Are you interested in our solutions? Schedule a meeting with a Consultant to talk through your strategy and understand how TEHRA-Trainer can help you to advance rehabilitation.